A New Perspective on Space-Time

The Shuttle and Missile Objection

This objection shows that maintaining the invariance of the one-way speed of light becomes untenable as soon as one takes into account the existence of physical bodies. It confronts physics with a crucial choice: either preserve its current models at the cost of logical inconsistency, or restore coherence by fundamentally rethinking the laws of motion and the very framework of space-time.

Even though this objection has elicited a wide range of reactions, including various forms of challenge, no attempt to demonstrate its lack of relevance could succeed over more than ten years. Yet an internal contradiction arising from a postulate is sufficient to call its validity into question — this is what is highlighted here.

Page Summary

- Preamble

- Introduction

- stakes of the objection

- Standard interpretation

- My interpretation

- Validity of the interpretation of the space-time diagram

- Space-time diagram of the shuttle and the missile, notes 1 and 2

- Physics-Online Forum (ThM)

- Extensions: block universe, twin paradox, Rovelli, etc.

- Further reflections, experimental test, conclusion and resources

- Terminology

Preamble

The shuttle and missile objection does not question the mathematical validity of the Lorentz transformations, but it challenges one of their possible interpretations: the invariance of the one-way speed of light. When this invariance relies on isotropy, it amounts to granting physical reality to simultaneity planes. From that point on, a simple change of reference frame may produce contradictions.

We must therefore place ourselves in a framework of absolute simultaneity, in which a universal present moment exists. Nevertheless, the rate at which time flows may differ from one observer to another.

From there, two possibilities arise:

1. The speed of light depends only on an ether.

2. It depends on the spatial configuration.

The second solution is the more plausible one. The proposed experiment — once the implications of the shuttle and missile objection are acknowledged — aims to reveal a violation of Lorentz invariance, suggesting that we must adopt a framework in which the speed of light depends on spatial configuration.

Whether one likes it or not, it is more coherent to think that the speed of light depends on spatial configuration than to maintain that it is invariant for all inertial observers. It is therefore legitimate to wonder why this possibility has never been seriously explored, and whether the dominant line of thought — by pursuing another path for more than a century — might have strayed from a more fundamental understanding of the Universe.

Introduction

My approach does not truly require validation from current science, because it simply reuses space-time diagrams that are already accepted. It merely shows — in an inescapable way — that since the birth of special relativity, science has never gone all the way in its interpretation of these diagrams.

Indeed, taking into account the actual existence of bodies within certain diagrams leads to contradictions. This forces us to reconsider the postulate of invariance of the one-way speed of light (see below). The need for a new conceptual framework for physics thereby comes into view.

Stakes of the objection

The shuttle and missile objection highlights a logical flaw that appears as soon as one considers the real existence of bodies within a space-time diagram. In this framework, the relativity of simultaneity leads to an internal contradiction, calling into question the postulate of the invariance of the one-way speed of light and, consequently, the relativistic representation of space-time.

Such a contradiction invites the search for a new foundational postulate to define the structure of space-time and, possibly, to consider the bases of a more general theory of the Universe.

Standard interpretation

The geometry of space-time determines causal relations. The isotropy postulate of the speed of light — that is, its invariance in a one-way trip for all inertial observers — underpins the geometric structure of Minkowski space-time.

This postulate implies the relativity of simultaneity as a physical property of the world, and leads to the conception of a block universe in which past, present and future events coexist, with causality constrained by light cones.

My interpretation

The isotropy of the speed of light — that is, its invariance in a one-way trip — implies a relativity of simultaneity that makes the existence of bodies depend on the chosen reference frame. This is what I call relativity of simultaneity at the physical level.

In other words, simultaneity is treated as a physical fact (and not simply as a synchronization convention). It forces us to consider that, in this representation of things, the bodies shown on the space-time diagram truly exist according to the simultaneity lines specific to each frame of reference.

However, as soon as an observer changes reference frame through acceleration, he modifies his line of simultaneity — and thus retroactively changes what exists for him. This ontological instability, revealed by the shuttle and missile objection, exposes a major physical contradiction.

It is therefore circular to claim that causality is not violated simply because it remains respected according to the definition provided by relativity itself. This principle of causality was constructed from the postulate of light-speed invariance; it is not an independent verification but a consequence of the postulate.

Validity of this interpretation of the space-time diagram:

The purpose of the Shuttle and Missile Objection is to demonstrate, that the speed of light cannot be physically invariant during a one-way journey between two points, in all cases and for all inertial observers (sense 1). One may also consider the invariance of the speed of light in the case of a round-trip journey (sense 2). This distinction must be stated with care; otherwise, the discussion risks addressing different issues. For the speed of light to be physically invariant in (sense 1), it is necessary to assign a physical meaning to the lines of simultaneity by associating them with the existence of moving bodies. This amounts to acknowledging the existence of bodies as it is revealed in the space-time diagram, which justifies a specific interpretation of the diagram, directly linked to the objective of the demonstration. The reasoning presented here aims solely to establish that the speed of light cannot be physically invariant under all circumstances (sense 1). Even if some may regard this point as minor, it actually constitutes an important step forward, as it encourages an evolution in our conception of space-time and opens the way to new experimental investigations. Questioning the physical invariance of the speed of light (sense 1) thus makes it possible to promote a more realistic interpretation and may lead to a renewal of the conceptual framework of physics.

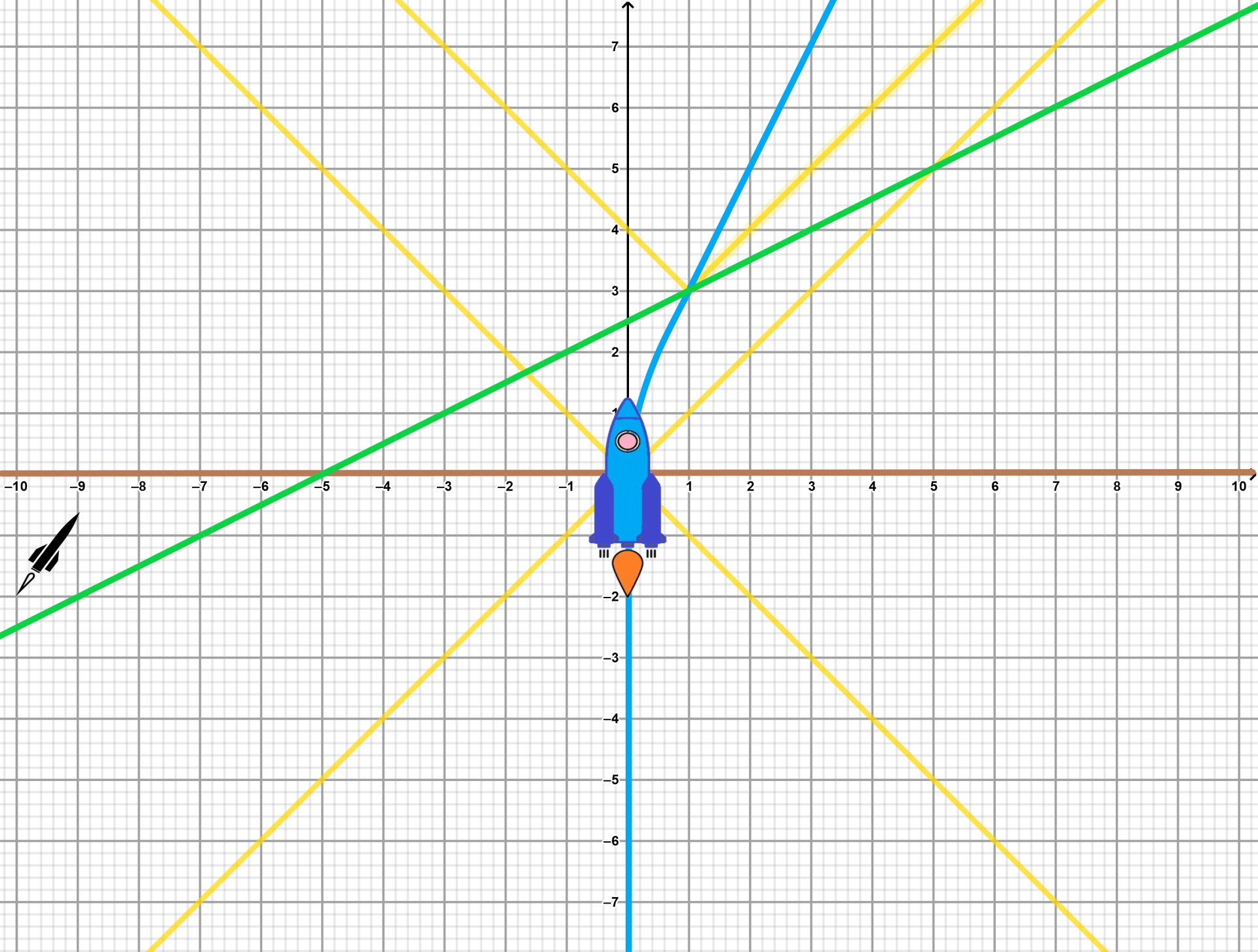

Space-time diagram of the Shuttle and Missile objection:

The images of the shuttle and the missile are from the Shutterstock image bank.

The spacecraft’s trajectory is presented here in blue, its line of simultaneity just before accelerating is colored brown, and its line of simultaneity just after accelerating is colored green. It can be seen that during the acceleration phase, the spacecraft’s line of simultaneity has undergone a rotation. The place where the missile base is located is indicated by the event "launching of the missile" indicated on the left by a picture of a small missile. The curved shape of the spacecraft’s trajectory due to its acceleration shows that the spacecraft is traveling at 50 per cent of the speed of light with respect to the launching pad, taken as the fixed reference value. For the sake of clarity, high spacecraft speeds have been depicted on the diagram, but this objection would be valid even at lower speeds, in which case one would have to take a larger distance from the missile base to the spacecraft. It can be seen that the "launching of the missile" event is taken by the spacecraft to have taken place both before its own acceleration, since it is placed below the brown line of simultaneity, and to have taken place only after its acceleration, since it is placed above its new line of simultaneity (the green line). This does not seem to be very plausible if we have accepted the existence of the missile on the basis of the spacetime diagram and the principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level. If the spacecraft’s control system has started before accelerating to perform a three-dimensional calculation of the missile’s spatial trajectory, it cannot possibly assume after accelerating that the missile does not yet exist (the missile is taken in this thought experiment to be assembled only at the very instant at which it is launched) (1). There do not exist two universe lines corresponding to the trajectory of the missile on the spacetime diagram:. Here we are talking about a three-dimensional calculation of the missile’s trajectory, which would be contradictory to what is shown on the spacetime diagram. The principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level suggested by the invariance of c therefore results in a contradiction (2), and since there is no third possibility, absolute simultaneity must be what exists at the physical level. And yet it has been established here that if there was absolute simultaneity, the speed of light could not be invariant in all possible cases involving inertial observers. This amounts to challenging the validity of the second postulate proposed in Einstein’s theory of special relativity.

Note 1: It is important to understand that, regardless of the outcome of the calculation, once the existence of the missile has been taken into account at the beginning of the reasoning, one cannot then conclude that it has not yet existed at the end. This is why it is not even necessary to determine whether the calculation is actually feasible: this fact alone already constitutes a logical contradiction.

Note 2: The principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level, as derived from the invariance of c and highlighted by the shuttle and missile objection, proves to be self-contradictory. It indeed suggests that what exists relative to the spacecraft (the missile) has subsequently not yet actually existed. The fact that the two events are separated by a space-like interval does not in any way affect the validity of this statement.

Consider a missile located 1 kilometer away from a spacecraft: if it has already traveled 100 meters after being launched, this remains a fact, regardless of whether the spacecraft accelerates or not. Now, if the missile is much farther away (for instance, billions of kilometers), and if it has also traveled 100 meters after being launched before the spacecraft begins to accelerate, The problem remains the same.

However, according to the theory of relativity, by applying the principle of the relativity of simultaneity, the temporal order of the two events — "launching of the missile" and "onset of the spacecraft’s acceleration" — can be reversed. By proportional calculations linking the spacecraft’s acceleration and the distance between the spacecraft and the missile, one could conclude both that the missile has already traveled 100 meters before the spacecraft’s acceleration and, in another frame, that the missile has not yet been launched after the spacecraft has accelerated.

This implies that if the spacecraft’s control system takes the existence of the missile into account, it would arrive at two contradictory results regarding the position, and even the existence, of the missile. There is no need to have all the equations of relativity at hand to follow this reasoning. It is enough to realize, first, that the invariance of the speed of light implies the principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level (Claim 1), and second, that in view of the shuttle and missile objection, this principle is self-contradictory (Claim 2).

Since we are in a spacelike interval, the shuttle pilot cannot perceive the event "missile launch." But in the thought experiment, we do not need to know whether the missile was actually launched. The reasoning is as follows: if the missile was indeed launched at that moment, the consideration of this event with this space-time diagram leads us to a contradiction.

To this day, and for more than ten years, no inconsistency has been demonstrated in a rigorous way in the reasoning presented on this page.

Physics-Online Forum (ThM)

It was ThM, from the forum Physique Oline, who provided me with the first space-time diagram representing my shuttle and missile objection. However, during the discussions, it was not acknowledged by ThM that the postulate of the invariance of the speed of light sense 1 implies the principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level, and that this principle requires, in the shuttle and missile objection, to take into account the existence of the missile based on what is shown on the space-time diagram. Indeed, it is precisely from this consideration that the validity of my objection becomes evident. ("Principle of the relativity of simultaneity at the physical level": see the chapter "Einstein’s Misinterpretation in his Train Thought Experiment" - assuming the invariance of the speed of light sense 1 - in the book “And He Was Hovering Over the Waters: Toward a New Vision of the Physical World ?”.)

Extensions: block universe, twin paradox, Rovelli, etc :

Relativity and the block universe — what physics avoids acknowledging Click here

"Twin paradox": two interpretations in conflict Click here

"Twin paradox": in search of a physical interpretation Click here

Carlo Rovelli, Étienne Klein, and time Click here

Marc Lachièze-Rey and semi-closed time loops Click here

Perspective on this research Click here

Relationship between philosophy and physics: a possible complementarity Click here

![]() "The Proof" of God's Existence from Motion Revisited Click here

"The Proof" of God's Existence from Motion Revisited Click here

Lines of thought for a new perspective:

Alain Bernard - Les Idées Froides (Fr) Click here

Grégoire - Livres et Science (Fr) Click here

The role of the forms of mass Click here

Evolution of the approch to length contraction Click here

Motion, Space, Mass, Causalité and the Equivalence Principle Click here

Experimental verification:

From conceptual reflexion to experimental verification Click here

Conclusion:

Conclusion Click here

Interview by Alain Pelosato Click here

Note on terminology: In this presentation, "relativity of simultaneity at the physical level" means that the relativity of simultaneity, as stated by Einstein, is a real aspect of the physical world, and not simply to a way of measuring or representing phenomena.

Philippe de Bellescize